Yooperlites, aka Glowdalites: what are they and where can I find them?

What’s a Yooperlite/Glowdalite?

Fluorescent Sodalite-bearing Syenites go by many names. The most common is “Yooperlite,” but we don’t care for this name since it suggests they can only be found in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. Though probably most common up there, these special fluorescent stones can be found across much of the Great Lakes and even scattered around the world from different sources. Thus, we prefer other names. The official name is not terribly friendly; fluorescent sodalite-bearing syenite does not roll off the tongue nicely. We at Michigan Rockhounds like to call our glowing sodalite rocks “Glowdalites.” It’s fun and a little hokey and we think it fits just nicely.

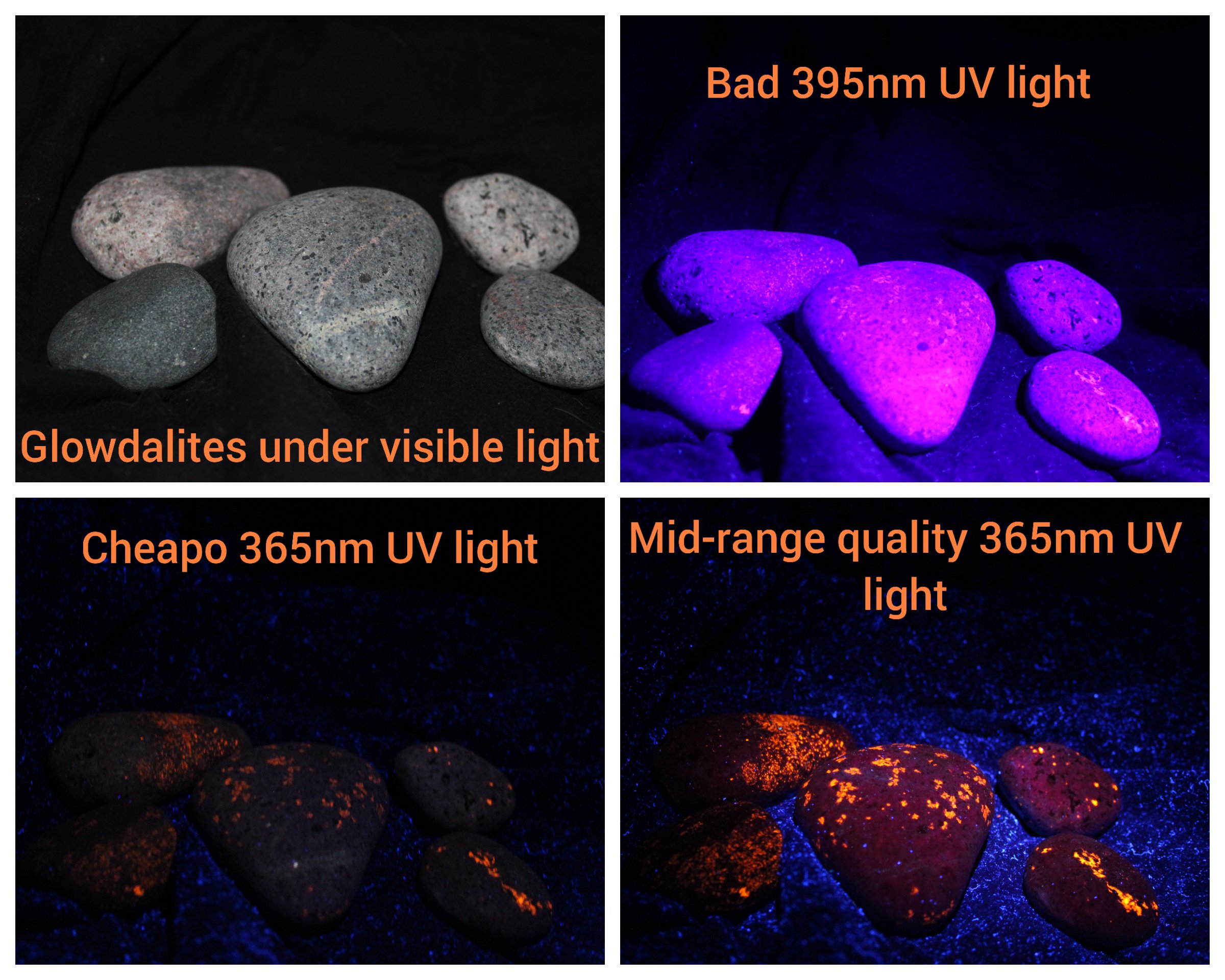

Glowdalites/Yooperlites can be found scattered across the shores of the Great Lakes and even inland. They are incredibly plain-looking under ordinary light and are virtually impossible to identify without a very good ultraviolet light. The cheapest and most common UV lights (or blacklights) are simply terrible- most are 395nm wavelength and while they do kind of cause some fluorescence, they really don’t work well. The best affordable lights are 365nm (same number of days in a year, so easy to remember) and those will show the glowdalites far better. Using a 395nm UV light is like using the 365nm UV light at night, but wearing sunglasses. You’ll find the most obvious ones, but you’re going to miss a whole lot.

There is currently something of a weird UV flashlight war going on in the glowdalite community and we’re not touching that with a ten foot pole. Our team has tested the flashlights in real-world conditions and the results are as follows: if you buy super cheap, you get junk. The most expensive are kind of overpriced, but higher end models do work a lot better than cheapo products. There’s not much difference between a $60 and $100 light, but a huge difference between a $60 and a $10 light so use that as a guide when shopping. We don’t recommend spending a fortune unless you can afford it.

Four identical photos of yooperlites/glowdalites. Top left is under visible light, the next three are photographed with identical shutter speed and aperture, revealing exactly what you’d see in each case. Top right, with the wrong 395nm light, is covered with purple light and shows almost no orange fluorescence. Cheap 365nm light is much better, but still very dim. The mid-range light is a massive improvement. For more comparisons, check out the gallery at the end of this article.

So how did glowdalites form and actually get here?

The glowdalites of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula- and probably all of Michigan- formed 1.1 billion years ago during a spectacularly violent geologic period when North America attempted to tear itself in two. At that time, the Midcontinental Rift (also called the Keweenaw Rift) formed, resulting in unimaginably large volcanic eruptions that generated more than 40,000 feet of lava rocks in some locations and 360,000 cubic miles of lava altogether. Just one of those eruptions produced a literal ocean of lava more than 1,700 feet deep at one time! It was an eruption that makes apocalyptic movies about Yellowstone look feeble.

This rift ultimately failed (which is obvious when you consider that North America is still intact). The Midcontinental/Keweenaw Rift was the largest rift in Earth’s history that didn’t eventually become an ocean, though it is mostly located beneath Lake Superior today!

Not at all far away, in Ontario near the modern shore of Lake Superior, another large body of magma was trying to reach the surface. That magma never quite made it all the way up to form another volcano. Instead, that magma hardened beneath the ground to form a type of granite called “syenite” and this one had a lot of a mineral called “sodalite.”

Remember that at this time, 1.1 billion years ago, everything on Earth was very different. The Upper Peninsula- besides not being a peninsula at all because there were no Great Lakes- was actually in the south and the Lower Peninsula was in the north and all of Michigan was just about on the equator! Those rocks remained buried for a billion years… from the development of complex multicellular life to plants and animals and dinosaurs… through it all, these rocks remained buried beneath the surface. Until…

The last ice age came and around 10,000 years ago enormous ice sheets more than 10,000 feet tall scraped across the land like a bulldozer, plowing up those sodalite-bearing syenites (glowdalites) southward and plopping them across the shores of what would eventually be the Great Lakes.

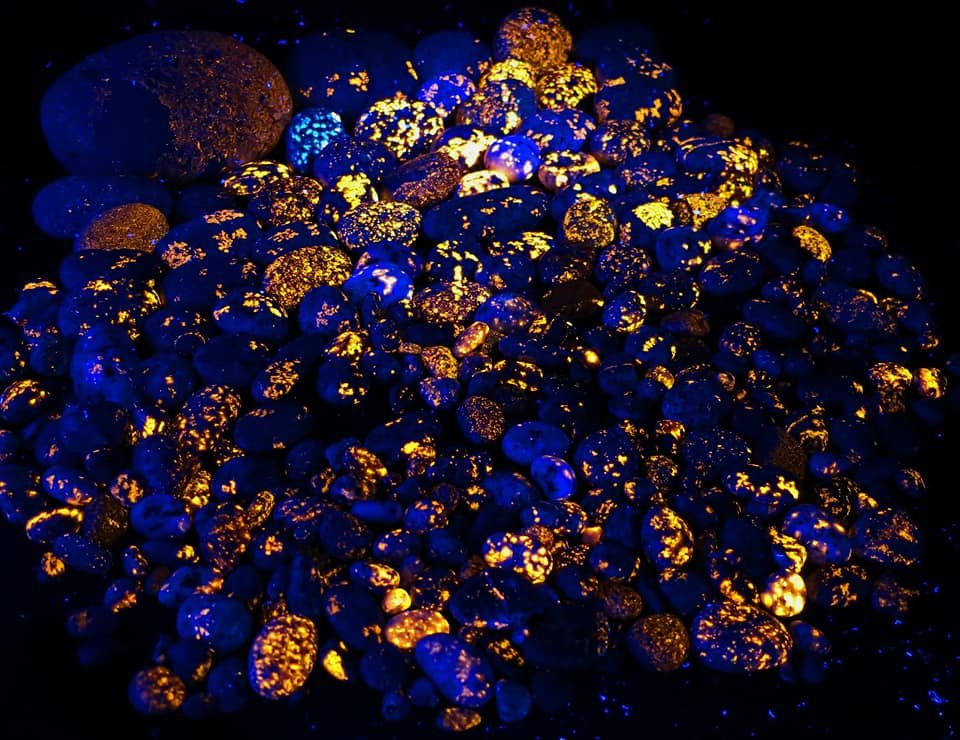

Photo Credit: Todd Warner

So where can I find glowdalites today?

That’s both an easy and hard question to answer. They were brought to Michigan by glaciers during the last ice age, so they were dropped mostly randomly across the state and you’ll never find a big “deposit” of them in any one place. With that said, though, there are places where you can really improve your odds of finding them. Firstly, I think most people know that the beaches are the place to go for searching out these rocks. What makes our shorelines special is simply the lack of dirt along the waterline. Those glowdalites are at the surface and freshly washed, making them much much easier to find!

Not all beaches are equal in glowdalite hunting, though. There are many where you simply won’t find them. There are two factors there. The first is sand. Anyone hunting rocks knows that a beautiful sugar sand beach is not the place to find stones. You need a rocky shoreline where everything is at the surface and unobscured. The second factor is the source of the rocks…

You can consider that there are 2 types of rocky shorelines in Michigan. Shores where the rocks have recently eroded from nearby cliffs and hills and shores where the rocks were left by glaciers thousands of years ago. Obviously, for glowdalite hunting, you want a shore where the rocks are mostly ones left by the glaciers. If there are cliffs or bluffs nearby or all of the rocks are limestone, that would be a bad sign for finding glowdalites. There may be a few scattered in the area, but they’re far more likely to be buried under tons of locally eroded rocks.

So where to find them? Technically they’re everywhere, but the best places are ancient rocky shores that are not near cliffs or hilly areas. Those shores will give you the best odds! And those “yooperlites” are more common in the Upper Peninsula, which makes sense because they were brought down from Canada so they’re closer to their source!

Photo Credit: Karah Keller

Why do glowdalites glow? What makes them so magically fluorescent?

Well, there’s something very special about the sodalite in this syenite lying about our shores. Sodalite ordinarily doesn’t really do much special, but this particular sodalite from Ontario is polluted or “doped” with disulfide- a species of sulfur. And that sulfur makes the sodalite fluorescent.

When you shine an ultraviolet light on that disulfide-doped sodalite, those energetic UV wavelength photons from your blacklight hit the electrons in the sodalite’s atoms and they jump to a higher quantum state- a higher energy level. That higher energy level, though, is unsustainable- it’s unnatural and it simply doesn’t last more than a fraction of a second. The electrons almost immediately drop back down to their lower energy state where they belong and when they do, they release that extra energy in a photon- a very specific orange wavelength of light that perfectly matches the amount of energy the electron just lost as it dropped back down into its place. That orange color you see when you shine a UV light on your glowdalite or “yooperlite” or sodalite-bearing syenite is called fluorescence and you’re witnessing quantum mechanics in action, made possible by a billion years of history.